"...He should study the face of his patient as the artist studies his picture, for he displays his talents not upon canvass, but upon the living features of the face; and of how much more importance is the living picture which reflects even the emotions of the heart than the lifeless form upon canvas. In raising the different muscles of the face the true artist will carefully avoid producing a stiff, restrained, or puffed appearance. He will place the prominences upon the dentures in their proper position, and make them of such form and size as to allow the muscles to rest, move or play upon them with perfect ease, that they may again reflect those sensitive emotions which tell of the inner workings of the mind.”

This is an excerpt from a treatise by Dr John Allen, father of the platinum base continuous gum denture. Dental Cosmos vol IX p. 485. Quoted in The Rise, Fall and Revival of Dental Prosthesis by CJ Cigrand, second edition Chicago 1893.

Read on to find out what's the history behind this continuous gum denture with platinum base crafted by Dr Ross almost a century ago.

Basic history of the prosthetic base

Ivory and metals have long been used as the bases of dentures. George Washington for example had a hippopotamus-based denture, another with bases of lead and yet another employing gold. The most popular metals used for dentures in the 18th and for most of the 19th century, included gold, aluminium, silver, tin, or some metallic alloy composed of multiple metals and including the aforementioned ones. Ivory was not the best material as it tended to absorb fluids and was terribly smelly.

By the late 1700s, French porcelain emerged as a substitute for animal ivory bases and human teeth in the fabrication of dentures. The main technological breakthrough was the ability to construct a denture from a single piece of enamelled porcelain. This was the first ‘continuous gum denture’.

The originator of this concept was a French apothecary, Alexis Duchateau, who had himself been wearing dentures made of hippopotamus ivory which had become stained from exposure to the chemical preparations used in his work and now tainted all he ate. After initial experimentation, attempting to overcome problems of distortion and shrinkage on firing, he sorts the assistance of a Parisian dentist, Nicholas Dubois de Chémant and together they modified the porcelain paste enabling it to be fired at a lower temperature to decrease shrinkage.

For the first time a denture could be made that was totally free from attack by oral fluids. The French revolution effected Dubois De Chémant's practice somewhat and he emigrated to London in 1792 securing the exclusive rights of manufacture of the porcelain pastes, now supplied by the Wedgwood factory.

Unfortunately, the all-porcelain continuous gum dentures were ill fitting, fractured easily and didn't look realistic. Not many could replicate the success of De Chémant due to the unpredictable behaviour of porcelain during firing. They fell out of favour very quickly.

About this time, dentures (or stoppings as they were called) of swaged metal, preferably gold, were being made on a model of the mouth. The dentist would have placed a plaster model, teeth up, in an iron ring and packed damp sand closely around it to fill the ring entirely. The model would then have been tapped out of this sand mould and the space it occupied filled with molten zinc to provide a hard metal cast, called a die. After dusting with French chalk to allow separation, molten lead would be poured over the die to form a softer counter die.

A shaped piece of flat gold sheet would then be beaten down on the zinc die using a horn mallet, a hammer having a head made of animal horn, which would not leave marks on the surface of the gold sheet. It was usual in those days to roll out gold sovereigns for this purpose.

Final swaging of the plate would then have been affected by sandwiching it between die and counter die and beating these two together with a sledgehammer. The technology was that of sand casting, as used in the cast iron industry, coupled with the art of precious metal swaging evolved by jewellers and silversmiths.

Bean teeth, rubber gums and flammable dentures

Teeth that could be fitted on soldered parts were carved ivory, human teeth, or the ‘bean teeth’ developed by Giuseppangelo Fonzi in Italy (1810). Inspired by Fonzi’s bean teeth, Claudius Ash in the UK (1854) and Samuel Stockton White in the USA began experimenting with making individual porcelain teeth. Porcelain was back in dentistry and this time it was to stay for over a century!

To form the denture base to go with porcelain teeth, many materials were used throughout the nineteenth century, including the old favourites hippo ivory and gold, but also tortoiseshell, gutta percha, ‘cheoplastic’ alloys and aluminium. The most important, if only for its role in ‘democratising’ dental prostheses, was vulcanite.

Charles Goodyear’s vulcanite patent in 1853 constitutes one of the most significant advances in prosthetic dentistry. By 1864 vulcanite became the base material of choice because, compared with the alternatives at the time, it was durable, affordable, strong, and light. It was easy to manipulate and repair, it did not absorb fluids.

However, it did shrink when processed and the colours did not match the natural gum. Pigments such as vermilion and lead was often added to the mix to obviate to give vulcanite a ‘pink gum’ colour. The use of vermilion hues in dentistry added significantly to the risks of mercury poisoning, for both patients and practitioners.

Around 1870 an even cheaper denture base alternative was on the scene…Celluloid. Its colour and texture closer to that of the natural gum than anything else available. However, it gradually turned black and green and distorted over time. Notoriously flammable, it also had an unpleasant taste and odour which was a significant disadvantage. Its manufacture involved the use of camphor, and that might have been the reason. Within a couple of decades, it was dismissed as an ‘unfortunate fad’ by contemporary dentists themselves. It also helped that the licencing arrangements for vulcanite use were finally scrapped, making rubber gum bases much cheaper. Nevertheless, celluloid is important in the history of dentures because it represents the first attempt to use synthetic plastic materials in dentistry.

Enamelled platinum bases

In the 1850s, the concept of continuous gum base returned in prosthetic dentistry, thanks to the American dentist John Allen, who devised a better porcelain cement formula and a construction aided by the concurrent invention of furnaces designed for the job. He was inspired by the work of Christophe Delabarre, a couple of decades earlier, who experimented with baking porcelain on a base of platinum. In his 1922 History of Dentistry, Taylor describes Allen’s technique as producing ‘the most beautiful of prosthetic restorations’.

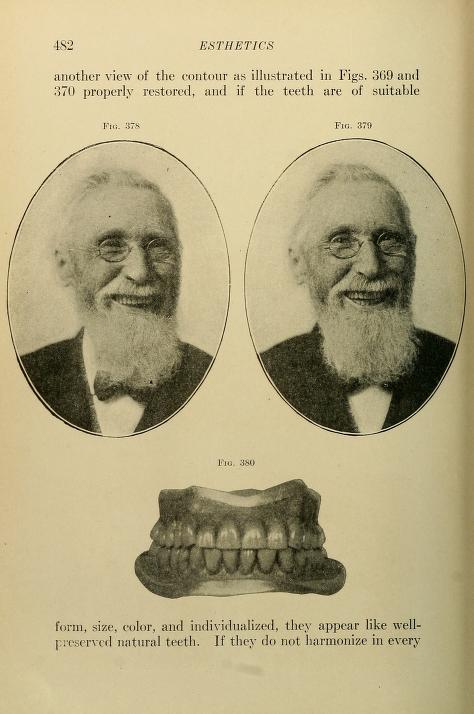

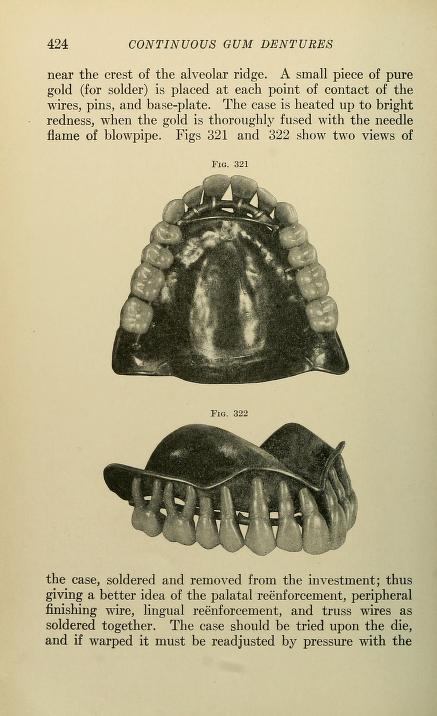

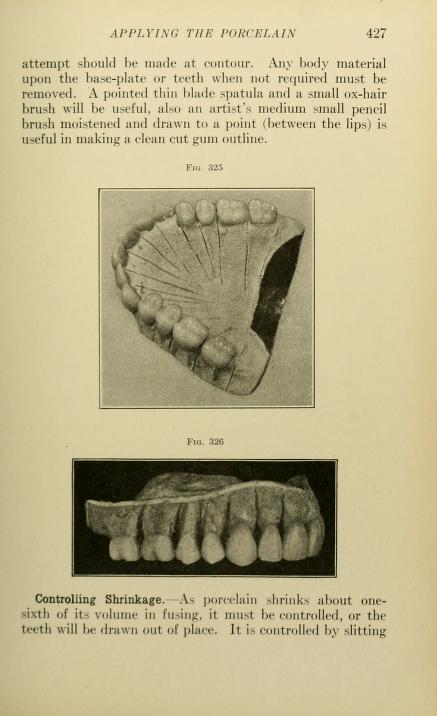

Individual porcelain teeth could be attached with solder to a platinum base plate with a porcelain cement using a furnace, and the plate then covered with a continuous layer of thin porcelain. The contours of the buccal flange and palatal tissues were formed using a low fusing porcelain following which a coloured porcelain approximating the colours of gingival tissue was brushed over the base porcelain and fused. All soldering investments and often the porcelain pastes were made by the dentist: it must have been quite a laborious process for each piece.

A distinctive type of tooth mould existed which had long porcelain extensions corresponding the roots. The tooth was thus capable of being ground to touch the platinum base irrespective of the amount of ridge resorption. Attachment was by a single platinum pin soldered to the platinum base. The process is described very well in GH Wilson's Manual of Dental Prosthetics of 1911 (view it at the Internet Archive).

In an article in the 1888 Dental Register, a WH Miller regarded the ‘cheap’ vulcanite dentures with disdain. While more expensive, he strongly advocated for the superior aesthetic qualities associated with a platinum-based continuous gum denture.

In 1892, Mr David Eden, eminent Brisbane dentist (he later founded the Queensland Odontological Society), seems to confirm this superiority. When interviewed about his travels back to the ‘old country’, Eden mentions attending a Dental Conference in Manchester, where he witnessed this technique: “[At the Manchester meeting of the British Association] a new machine for moulding work for continuous gum purposes was also introduced and I was so taken with the instrument that I brought one out with me. The process is new to me, and it enables the work to be done so well that the resemblance of the artificial gum to the natural gum is complete.” The machine Eden refers to might have looked like the furnaces offered by Claudius Ash in their 1899 catalogue:

The ‘recipe’ for continuous gum work evolved over the years. In 1894 the American Textbook of prosthetic dentistry (by Charles Essig) offered a few formulae for bodies and gum enamel, with the original one by Allen now being ‘out of use’ (pp. 223-224). Dr Hunter’s formula included the use of asbestos, to be ground very fine. Asbestos fibres were in common use at that time, with the opening of commercial mines in the late 1800s.

The 1911 Manual of dental prosthetics by GH Wilson offered the clearest explanation of the process to create a continuous gum denture with enamelled platinum, including images of the steps involved (pp. 416-429) https://archive.org/details/manualofdentalpr00wils/page/416/mode/2up?q=continuous+gum

Continuous gum work was considered especially clean, aesthetically pleasing, and healthy. The platinum base was incredibly resistant to bodily chemicals. Despite these advantages over other denture types, there were a few disadvantages as well. These dentures were heavier, more likely to fracture, time-consuming, and extremely difficult to construct. Vulcanite and eventually plastics confined this distinctive technique for base plates to the forgotten history of dentistry for good.

Nevertheless, platinum continues to be used in dentistry as substrate for porcelain crowns. The marriage of platinum and porcelain in dentistry is still a strong bond.

Dr Ross' platinum base denture

Jack Ross was a renown Rockhampton dentist, as well as a passionate horse trainer, with a past as gold tailings picker and wire-walker in the circus.

In 1991 his son Dr Don Ross, also a dentist, shared with ADAQ his father’s eclectic life story and uncommon expertise in crafting this type of denture:

“When he installed the first electric generator in Rockhampton, he was able to create his continuous gum dentures. With the use of his electric furnace he fused the enamel porcelains. This gained him recognition not only throughout Australia but among the dentists in Harley Street London.

“The expertise and artistic ability required to construct a continuous gum denture is enough to make the most courageous cower. First, one must swage a sheet of platinum over a zinc die made from an impression of the ridge involved. A thin platinum wire is then soldered around the periphery of the platinum base with gold solder. Once the bite is registered, and the base articulated, platinum pin porcelain teeth (imported from America) are set up in wax. The pins must touch the platinum base as these must be soldered to the base with gold solder. This is made possible by the making of an investment wall around the teeth after the setup has been completed and the wax has been boiled out. The base is then packed with porcelain enamel powders of various gum colours mixed with water to make a paste and placed on all areas except the tissue-contacting surfaces. The work is placed in an electric furnace; my father used DC (direct current arc) furnaces, and quite often would spend all night checking the correct firing and cooling of the piece. Platinum is tolerated remarkably well by the tissue; I have seen this type of platinum denture made by father still well fitting in the mouth after twenty years with practically no resorption present.” (ADAQ Newsletter, 1991).

We are unable to substantiate Don’s claims of Harley Street recognition as no trace of his name has been found in the contemporary journals we searched so far. However, the denture in our collection is indeed a masterpiece. A note: the blistering present on the palatal surface of this denture may have been due to traces of borax used as a soldering flux. The additional firings were advised to build the denture to the appropriate contour.

References:

Essig CJ. The American text-book of prosthetic dentistry : in contributions by eminent authorities. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co.; 1896.

Cigrand BJ. The rise, fall and revival of dental prosthesis. Second edition, revised and enlarged. ed. Chicago: The Periodical Publisher Co.; 1892.

Taylor JA. History of dentistry; a practical treatise for the use of dental students and practitioners. Philadelphia: Lea [and] Febiger; 1922.

Wilson GH. A manual of dental prosthetics. Philadelphia: Lea [and] Febiger; 1911.